- Home

- Raymond Benson

The Black Stiletto Page 2

The Black Stiletto Read online

Page 2

Outside, I sat on the wooden front porch and held the book in my hands. What was I going to learn from reading it? The truth about my father, perhaps? Mom had always told me his name was Richard Talbot and that he’d died early on in the Vietnam War. I never knew him. The really odd thing about it was there were no pictures of him in the house—ever. I don’t even know what he looked like. When I asked my mom about it when I was teenager, she simply said she couldn’t bear to look at his face after he’d died. She’d gotten rid of all his photos. I asked her about his family—my grandparents or any uncles, aunts, or cousins on his side—and she replied that there weren’t any. The same with her own family. We were all alone.

I accepted all that as gospel.

I flipped through the diary, afraid to start reading.

My mom was the Black Stiletto.

I still couldn’t wrap my brain around it. This was big. It was bigger than anything I could imagine. It was tantamount to finding out the truth behind JFK’s assassination or the identity of the Green River Killer. The Black Stiletto was a world-famous legend, an international icon of feminist strength and power. And no one knew who she really was except the Stiletto herself. And now me.

Her existence had become the stuff of myths, just like that pinup model Bettie Page, who had posed for underground nude photographs and films in the fifties and then dropped out of sight. In the eighties and nineties, pop culture had “rediscovered” Page and her images sprouted everywhere—even though the woman herself was nowhere to be found. The media exploited Page’s likeness without her permission through movies, comics, and magazines—and then she finally made herself known. The elderly former model had been living quietly in seclusion, completely unaware of the attention she’d been getting until a friend pointed it out to her. Only in the last years of her life did Page see any profit from the use of her youthful image.

The same thing had happened to the Black Stiletto.

She was active in the very late Eisenhower years and some of the sixties, an underground heroine who made a name for herself as a vigilante. Although she was wanted by the law and would have been arrested had she been caught or her secret identity been revealed, the Black Stiletto was a competent and successful crime fighter. She battled common crooks, Communist infiltrators, the Mafia—and was responsible for their capture and, in some cases, their deaths. The Stiletto first operated in New York City, but when the police came too close to catching her, she moved to Los Angeles.

Where I was born.

And then she’d inexplicably disappeared and was never heard from again. No one came forward with knowledge of who she really was and most people thought she’d probably died. Why not? She was involved in dangerous, high-risk situations. It made sense that she’d been fatally injured or even arrested and sent to prison without the authorities knowing who they’d really locked up. For a while it was one of those big mysteries like “who shot JFK?” What happened to the Black Stiletto? Where is she? Is she alive or dead? WHO was she?

A decade passed and people tended to forget about her until the mid-eighties, when a fledgling independent comic-book publisher began a fictional series about the costumed crusader. They proved to be extremely popular and sold all over the world. The History Channel did a documentary biopic in the early nineties that consisted mostly of speculation, as I remember. There was at least one biography published, but of course it contained nothing about the Stiletto’s personal life. It was simply an account of everything that had been documented about her in the newspapers. Then came the toys and other merchandise—action figures, videogames, board games, Halloween costumes, you name it. A lot of manufacturers were making millions off the Black Stiletto and there was no one to defend her interests.

A feature film starring Angelina Jolie came out in the late nineties, before the actress had become a huge star. The picture was a hit but had very little to do with the real Black Stiletto. It was all fantasy with lots of gunplay, explosions, and unbelievable stunts. The real Black Stiletto was much more low-tech than what was portrayed in the movie. Still, it captured audiences’ imaginations. There was talk of a television series, but it never came to pass.

Like most people, I, too, was fascinated by the Black Stiletto. If I’d been younger when the comics came out, I probably would have bought and read them.

Apparently, Mom was well aware of what was going on, seeing there was a little collection of ephemera in the closet. She never said a word. She could have capitalized on her past and made a fortune. But instead she lived quietly and in obscurity here in the Chicago suburbs until the onset of her illness.

I couldn’t wait any longer. I opened the first diary and started to read.

2

Judy’s Diary

1958

July 4, 1958

Dear diary, I thought maybe I should start writing all this stuff down. When I was a little girl I kept a diary. I wrote in it for about three years, I think. I don’t know what happened to it. I guess it’s still back in Odessa, sitting in a drawer in my old room. If my old room still exists.

I’m chronicling everything that’s happened to me lately, just in case something bad happens. I’m not sure if I really want the truth to come out, but here it is. So much has occurred in the last six months. In a way, I’m more famous than the mayor of New York City! Well, not me, Judy Cooper. The Black Stiletto is. No one knows Judy Cooper is the Black Stiletto, and I hope to keep it that way.

Funny, I can hear Elvis singing his new song, “Hard Headed Woman,” on someone’s radio in the distance. He could be singing about me, ha ha. Whoever has that radio must be playing it awfully loud, ‘cause right at this moment I’m sitting on top of the Second Avenue Gym building and watching the fireworks on the East River. Or it could be just ‘cause my hearing is better than most people’s. Sometimes it’s hard for me to tell.

The gym is my home and has been for quite some time. Freddie Barnes runs the place. He’s a trainer and former boxer. He lives above the gym, and so do I. He’s been letting me live in a room above the gym for a few years now, and I pay for it by working for him in all kinds of capacities. I started off being the janitor—cleaning and sweeping and washing the disgusting toilets in the men’s locker room. Then he made me a cashier and assistant manager. Now I get to help with the training because I’m pretty good in the ring. Not many women are. Not many women do that kind of thing. It’s fun. I like it. I hope to someday start my own self-defense program for girls. I don’t want anyone growing up to be victims. No one should have to experience what happened to me when I was thirteen.

Right now I’m twenty years old. I’ll be twenty-one on November 4. I’ve been in New York since I was fourteen. I guess you could say that’s when my life really started, because before that I was in hell. Luckily, I managed to escape.

I suppose I should take up the first part of this diary with the past to bring it up to date. I’ll spend the next few days writing and filling in the story and then, when I’ve reached July 4, 1958, I can just make entries on a daily or weekly basis—or whenever I feel like it.

So here goes, dear diary. This is my life, and I warn you—some of it ain’t pretty.

Like I said, I was born on November 4, the year 1937, in Odessa, Texas. My parents named me Judith May Cooper. My father, George Cooper, was an oilman, a roughneck, which was the only kind of work he could get during the Depression. He worked on the oil rigs. I don’t know how good he was at it. He’d moved to West Texas when they discovered oil there in 1926. My mother, Betty, cleaned houses. She was no better than the colored ladies who did the same thing. I actually think she brought more money home than my dad. It was a tough time. We were on the low end of middle class, or maybe the upper end of lower class. All I know is we lived in a shack on the edge of the town. There were still a lot of people who didn’t have jobs at all.

I had two older brothers—John was five years ahead of me, and Frank, three years older than me. Growing up with two o

lder brothers made me a tomboy from the get-go. All I wanted to do was play with them and do boy stuff—play ball, do sports, act out cowboys and Indians—you know, boy stuff. One of our favorite games was playing “Americans vs. Japanese,” in which we’d take turns being the army, navy, or marines, and the other team was the Japs. I was particularly good at sneaking up on the Japanese “bunker” and surprising them. I think I always won when we played that game. So, yeah, I was really into doing stuff with the boys. Whenever I did play with girls I was bored silly. If I had dolls, I usually ended up breaking them or letting my brothers use them for target practice with their B-B guns. Sometimes I shot at them, too, ha ha. We didn’t have any pets, although there was a stray cat that used to come around and I’d feed her. She didn’t really like me, though. I’d try to pet her and she’d hiss and run away. I stopped feeding her and she didn’t come around anymore.

I barely knew my dad. When the war started, he enlisted. It was 1942, right after Pearl Harbor, and he went out and joined the navy. I was still pretty young—I was four—so the last image I had of him was him waving goodbye to us as he caught a bus to take him into town. From there he went to boot camp and then was shipped off to the Pacific somewhere. He was dead just a few months later, one of the three hundred or so Americans killed in the battle of Midway. So, I never saw him again.

Things went downhill for us after that. Mom tried to make ends meet as best she could, but our family sank deeper into poverty. Looking back, I can see how bad it was, but at the time I was just a precocious little girl, always getting in trouble, rough housing with my brothers and their friends, and driving everyone crazy. By the time I started first grade at South Side Elementary, I could beat up most of the boys in the neighborhood if I wanted to. I was a tough little hellion.

Around the time I did start school, we lived near the corner of Whitaker and 5th Street. It wasn’t a shantytown, but we weren’t far from one. The Negroes lived just a few blocks south from us, across the tracks. I was too young to let it bother me. I walked to school with my brothers—John was in sixth grade and Frank was in fourth when I started first. It was a crappy school, that’s for sure. Everyone who went there were oil field roughneck kids. No one with a whole lot of class, if you know what I mean. I didn’t have many friends in school. I was a social outcast. Too much of a tomboy for the girls and too much of a bully for the boys, ha ha!

My best friends were my brothers, and it got to where they thought I was weird, too. Pretty funny when I think about it now. I loved my brothers, though. They usually stuck up for me when I got in trouble, which was a lot. Unfortunately, they didn’t stick up for me when I needed them the most, and I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to forgive them for that.

I guess people might say I was an angry child. I don’t know what I was so angry about. I just liked to pick fights. There was a lot of aggression inside me, a temper that could be ignited on cue. There still is. I was born with it and I needed some kind of outlet. It drove my mom insane, or at least it drove her to drink. Well, it probably wasn’t all my fault, but I know I was a handful for her. She did start drinking, though, after Dad died. She wasn’t much fun to be around.

Despite all that, I was a good student. Learning just came naturally to me. I wasn’t so hot at math, but I enjoyed science and history. I was particularly good at reading and writing, which is why I kept a diary for a while. I found that I liked reading books, so if I wasn’t outside playing football with the boys, I was inside with the latest Hardy Boys or Nancy Drew adventure. I wasn’t into comics, but my brothers were. Every now and then, I’d look at their Superman comics, but they just didn’t do it for me. I thought they were silly. I like my adventure yarns to be a little more credible, set in the real world. Early on I had trouble with the physical act of reading, so my mom took me to a doctor to have my eyes examined. I remember she wasn’t happy about paying the money for a pair of glasses, but I guess I needed them at the time. From then on, I saw perfectly—I just looked like an idiot. I hated wearing glasses and it only got me into more fights in the neighborhood when the other kids teased me.

Life pretty much remained the same until I turned twelve. When puberty kicked in, strange things started happening to me. I don’t mean the usual strange things that happen to all girls—you know, starting periods and growing breasts and all that—but other stuff that wasn’t quite normal. For one thing, I discovered I didn’t need my glasses anymore. I could see without them. Twenty-twenty. In fact, my eyesight was better than perfect. I could read signs at distances most people couldn’t. And I could decipher fine print without a magnifying glass. Another thing that changed was my hearing. Before I hit puberty, I could hear fine, but afterward everything was amplified. I could hear people whispering from across the room. It was really weird. I could understand conversations taking place in another room. I could hear them through the wall almost as if the people were in the same space as me. One day I went to the school nurse to ask her about it. She recommended I get my ears checked by a doctor, but I never did. I wasn’t worried about it or anything. Actually, I thought it was great. I could eavesdrop on kids in the lunchroom, where it was usually pretty noisy, and I heard everything they said. I was able to play “he said, she said” better than anyone!

Something else changed that I didn’t really notice until a little later. When something was going on behind me, I knew what it was. You know that expression, “eyes in the back of your head”? That’s what it was like. No one could sneak up on me. I could simply sense when someone was in back of me. And if I was walking down the street, I could anticipate if somebody was around the corner up ahead. And sure enough, there was.

Another ability I developed, if you can call it that, was an acute intuition. Somehow, I just knew when my brothers were lying about something. And I’d catch them at it, too. I’d say, “Frank, you’re lying. I can see it in your face.” We’d argue for a minute but I’d point out the flaws in his argument, and eventually he’d admit he was indeed lying. By the same token, I could tell when someone was being honest. Just within a few minutes of talking to a stranger, I knew if he or she was a good or bad person. If someone had a good heart, I knew it. Or if they harbored hate or anger, I could tell that, too. I should have gone to Las Vegas and become a card gambler. I probably would’ve won a million dollars, ha ha!

At the time, I didn’t know if something was wrong with me or not. I was afraid to talk about it or tell my mother. She’d just get upset at having to take me to the doctor again. And it wasn’t like it was hurting me or anything. I realized it was special. I was different and I liked that. Now that I’m twenty and can look back objectively at twelve-year-old Judy, I understand that these heightened senses are unique to me. Nobody else I know of has them. These abilities certainly help me when I’m the Stiletto. I couldn’t put on a costume and do all the climbing and jumping and fighting I do without this extra awareness. I tried reading about it in books on anatomy and psychology, but there was nothing I could find. I finally attributed it to the onset of puberty and the fact that I’m a female animal. Like a lion or tiger that protects her cubs. That sounds silly, I know, but think about it—all the senses an animal mother uses in the wild to protect her young—and herself—are these same things. Seeing, hearing, alertness, instinct.

I guess I’d make the perfect mother—ha ha! Well, maybe someday. That’s certainly not on my horizon anytime soon.

Well, all this new stuff made me act even weirder, as you can imagine. My mother and brothers noticed I was different, but they just chalked it up to my becoming an adolescent. Nevertheless, I felt as if they all shunned me a little. I was an oddball. A freak. And so, life in the house became more and more uncomfortable and strange. Not only was I a social outcast at school, but I became one at home, too.

Anyway, once all this started happening and I realized I could control it, I started doing more sports at school—and I was darned good. I especially liked gymnastics. I was on the school

team for a little while and outdid everyone. It was like the uneven parallel bars were a part of me. I practically floated on them. The coach was amazed and wanted me to compete in competitions. But I had a bad temper and would get mad if I wasn’t the center of attention. I was a real bitch, if I do say so myself, and so I didn’t last very long in a team configuration. So I practiced on my own, getting to where I could swing, handstand, dismount, and flip with the best of ‘em. On a balance beam I was like a cat. I was agile, light, and could contort my body into a pretzel. So, yeah, I was athletic and I was good at it. There’s no doubt that all this was an asset when I became the Black Stiletto.

Something occurred in the fall of 1950, while I was still twelve, that may have been instrumental in my deciding to become a costumed vigilante later. It was an event at which all of these new senses came together and drove home the notion that I was different and could use my “powers” to help people.

It was a weekend, so I wasn’t in school. I liked to take walks by myself out in the oil fields. I’d take a bus out that way and then just go on a hike. I enjoyed watching the pumpjacks as they rocked back and forth. The derricks were majestic and looked like sentinels against the flat horizon. It was solitary and comforting. It was a refuge away from the awkwardness at home. Anyway, I was walking along, lost in my thoughts, when I heard what sounded like a crying baby. My ears pricked up, I mean literally, I felt the muscles in the side of my face stretch. Out in the fields it would normally be difficult to tell where a sound was coming from. With the wind and sheer flatness of everything, noise tended to come from every direction. But not for me. I knew exactly where that baby was. The infant was over a hundred yards away, near one of the pump jacks.

What was a baby doing in the oilfields? I wondered. Had one of the roughnecks brought his kid with him to work and left the child unattended? I was too young to fathom that someone might actually abandon an infant. It didn’t cross my mind

The James Bond Bedside Companion

The James Bond Bedside Companion The Black Stiletto's Autograph

The Black Stiletto's Autograph Blues in the Dark

Blues in the Dark Zero Minus Ten

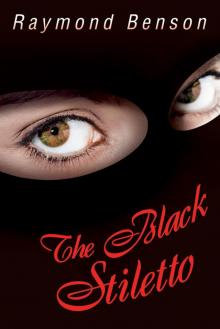

Zero Minus Ten The Black Stiletto

The Black Stiletto Doubleshot

Doubleshot High Time To Kill rbb-3

High Time To Kill rbb-3 Bond Movies 07 - Die Another Day

Bond Movies 07 - Die Another Day The Facts Of Death

The Facts Of Death Midsummer Night's Doom

Midsummer Night's Doom Blast from the Past

Blast from the Past The Secrets on Chicory Lane

The Secrets on Chicory Lane High Time To Kill

High Time To Kill The Black Stiletto: Black & White

The Black Stiletto: Black & White The World Is Not Enough jb-1

The World Is Not Enough jb-1 Zero Minus Ten rbb-1

Zero Minus Ten rbb-1 In the Hush of the Night

In the Hush of the Night The Black Stiletto: Stars & Stripes

The Black Stiletto: Stars & Stripes Bond Movies 06 - The World Is Not Enough

Bond Movies 06 - The World Is Not Enough The Rock 'n Roll Detective's Greatest Hits - A Spike Berenger Anthology

The Rock 'n Roll Detective's Greatest Hits - A Spike Berenger Anthology Never Dream Of Dying

Never Dream Of Dying